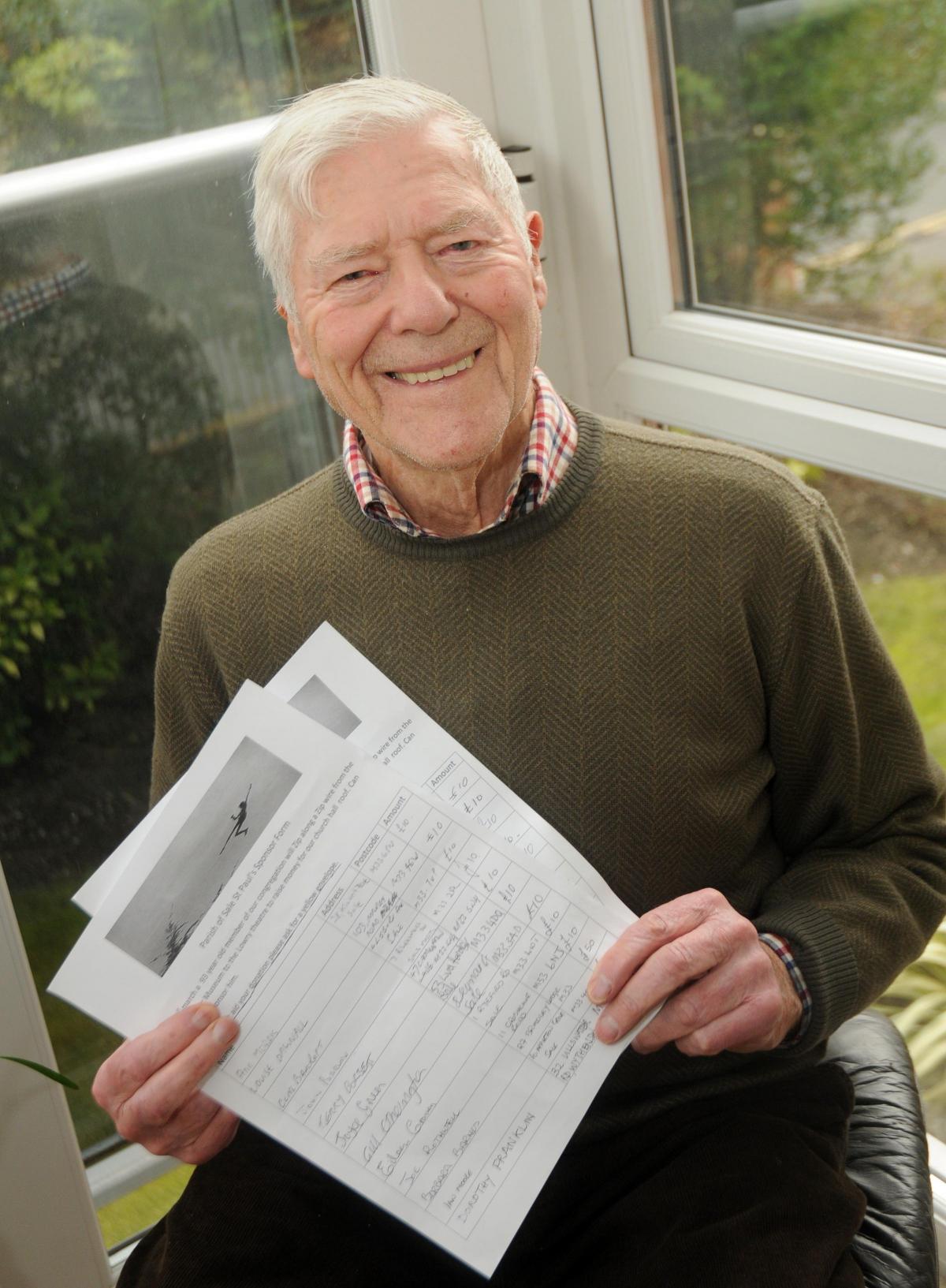

WHEN Frank Tolley leapt from the top of the Imperial War Museum North on Saturday, it was far from the most terrifying airborne ordeal of the 93-year-old’s life.

The Sale resident became the oldest person to complete the famous zipwire over Salford Quays last weekend, but the Second World War Bomber Command veteran had already gained his head for heights over occupied Europe, 70 years ago.

As the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Britain approaches, he told Messenger about his time in the RAF – the camaraderie, adventure and fears he experienced with his crew.

“I joined up aged 19 in 1940,” remembered the former Lancaster Bomber crewman. “I was a ground gunner to begin with at RAF Bramcote.

“It happened that I was there when the Germans came over on their way to Coventry. They were too high for our cannons; out of range.

“The next day I went home for a couple of days to Birmingham. I hitch hiked into Coventry and saw the damage. I thought: ‘hell’s bells, if this war is going to be won, it’s going to be won from the air’.”

Frank accepted an offer to train as a pilot before arriving at Heaton Park, Manchester, for his grading.

Selected as a bomb aimer, he was sent to Canada, arriving in North American on the requisitioned Cunard Line ship, Mauretania.

Based at RCAF Fingal on the north shore of Lake Eerie, he then went to Toronto to do six weeks Navigation Course.

Frank was now a ‘jack of all trades’ he explained – and would be able to leave his bombardier sight in the Lancaster’s nose and take over if either the navigator or pilot ‘went for a Burton’.

Returning to Moreton-in-Marsh, Frank met Australian pilot Bruce Windrim, who would become a great friend and a member of the seven-strong Lancaster aircrew Frank served with until the end of the war.

“We all got one very well together. “I was the old man of that crew at 23. The gunners were 18.

“The pilot turned 22 on the way back from an operation and, at midnight, the gunners started to sing ‘happy birthday’. He told them: ‘cut that out. We’re not back yet!’

“We had a lot of fun, but I can assure you that we were ordinary bods. We were not heroes at all.

“We were had a job to do, and were scared on a number of occasions.”

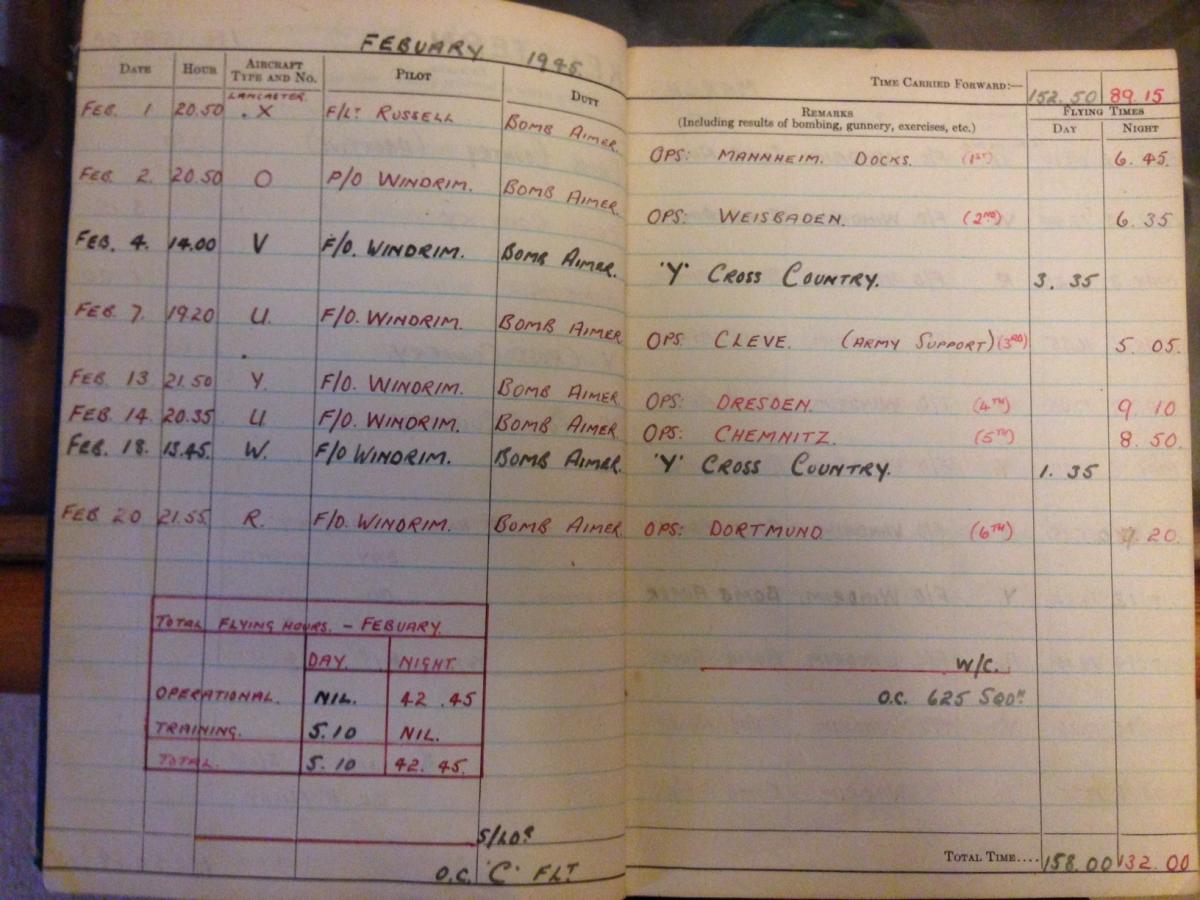

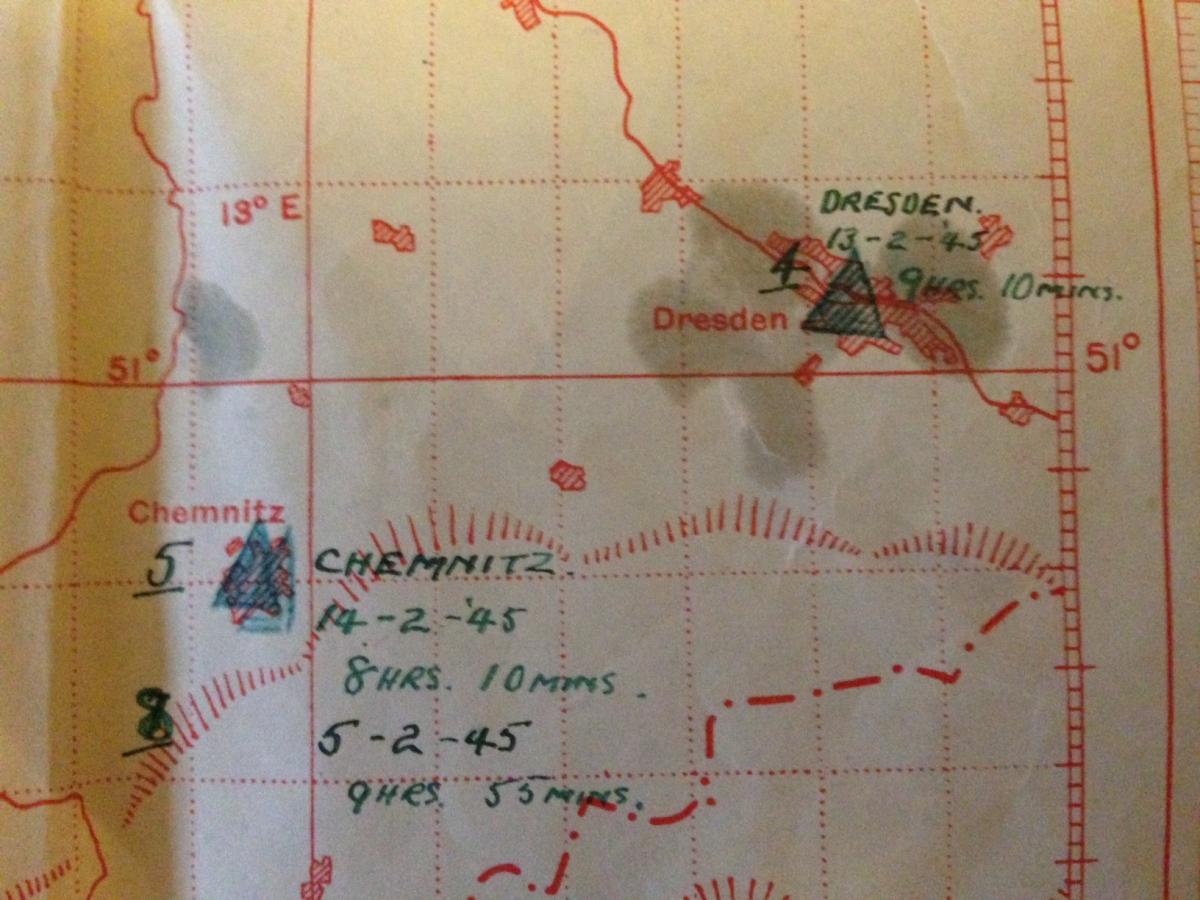

Flying out of RAF Kelstern, Frank completed 22 missions over Europe, including the notorious bombardment of Dresden.

“We were in the third wave,” he remembered. “When we got over there it was just one mass of flame. You could see it for miles off.

“I didn’t use the bomb site at all. There was nothing left to aim at. I just pressed the switch and released them.

“From the debriefing that followed they realised what had happened – the firestorm that had been created.

“There’s no doubt about it. History will point out that we were war criminals. You think of the 25,000 that were killed. It’s damned haunting. But yours was not to reason why.”

Back on base, Bomber Command’s low survival rate provoked gallows humour.

“We’d joke that those condemned to die would get to choose a last meal, but all we got before we went up was bacon egg and chips. We used to call it the condemned man’s breakfast, because we didn’t know what was going to happen.”

In one 35-hour period alone, he flew back to back missions over Dresden and Chemnitz, with barely a moment’s sleep between 18 hours flying time and briefings.

“Some others had it so rough that they couldn’t go on. They should have been taken off and given six weeks leave to get them mentally fit. But if you finished you had your documents stamped ‘LMF’ – lack of moral fibre. No-one wanted that.”

Sat in a Perspex dome in the Lancaster’s nose, Frank used airspeed, altitude, compass reading, wind speed and direction to determine the bomb release.

Talking directly to the pilot to keep on course, the plane would surge upward from the rapid weight loss when the bombs were away.

After checking there were no ‘hang-ups’ in the bay – which would have required manual bomb release – Frank would close the doors and head for home.

Frank remembers the ‘miracle’ of a bombardier he met walking across base with a sheet ‘torn to ribbons’ – the remains of a parachute that he’d used as a pillow while hunched over the bomb sight, and which had taken the full impact of a flak blast that ripped open his Lancaster’s nose.

Another time, a fellow crewman was ordered to stop reporting friendly planes shot down during a night of heavy losses over Nuremburg, for fear of crushing morale.

Taking over at the back when the rear gunner’s heated jacket failed was another tense moment, as was coming under friendly fire while returning home.

“On one occasion I had to take the plane around again over the target. This was when they had cottoned on to us – illuminated by the search lights.

“The crew played hell with me. They were saying: get us to the bloody thing and let’s get away from it!’”

Another time, getting ready to release, Frank saw a fellow Lancaster pass underneath his plane, ‘twenty feet below us, its starboard wing a mass of flame’.

“I held a split second for it to go by. I was thinking ‘if there’s a chance of them getting out...’ But that split second delay meant we missed the target.”

Demobbed in 1946, Frank regularly gives talks to schoolchildren about his experiences and his belief in diplomacy, not war, being the key to resolving conflict.

He volunteers at Imperial War Museum North and his charity zipwire last weekend has raised money for Cash for Kids, as well as St Paul’s in Sale.

He added: “On my first operation, when I’d released the bombs, it occurred to me: ‘I’m breaking the sixth commandment’.

“I was watching these bombs go down. It was at night time and I heard a voice. It said: ‘what’s happening? When can we close the damned bomb doors, it’s getting cold up here!’

“I quickly looked across, saw there were no hang ups in the bomb bay and called: ‘close bomb doors’.

“All aircrew, no matter what command they were in – bomber, fighter, transport, whatever – they were all just doing what they were directed to do.

“Now, if I get something haunting on my mind and want to get rid of it, I tend to write poetry.

“I was just an ordinary youngster. I didn’t think about it until later.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel